Digging into the Past #1: Knut Hamsun

I have to go all the way back to last September (almost 12 months ago now) to share my thoughts on this, the first book of a new series for me: Digging Into the Past. This short series will include a paragraph on each of the novels or short story collections I have read in the past year while being away from this blog (oh please, do forgive me). So, without further adieu…

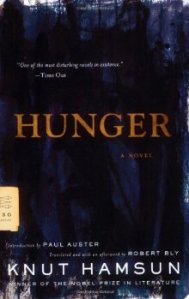

Hunger, by Knut Hamsun

I didn’t realize what was happening in this novel until I neared the end, but it is a piece of work that I have thought back upon several times since then. What one witnesses in this tightly written work is the destruction of a man – a dignified man – by the experience of hopeful and then hopeless unemployment and homelessness. It is a tragic tale. Compellingly written. Perhaps one of the great works of the early modernist period (but I’m not expert, and can’t really say that I’m all that familiar with the early modernist period). What I can tell you is that this work demands a high degree of comprehension – the evidence of the man’s disintegration is provided, but the dots aren’t connected for you – and will produce in you the highest degree of compassion for the homeless and the unemployed. And then it will haunt you, and, if you are like me, direct you to other works by this highly imaginative author.

Sometimes you e…

Sometimes you encounter a voice in literature that stuns you completely and totally – that writes prose the only way that it should feel like it was ever written for you, the reader. You, the individual reader. It is an incredible feeling. I’ve felt it rarely. But it can be incredible when you do.

And I think I have a couple times in the past year, as I have continued my search for new authors to connect with. Nadine Gordimer has entered my life – and she writes with the most generous selection of perfect words imagineable. Vladimir Nabokov has submerged me into his world of awe and energy and tension – unbelievable tension. And then there is Jose Saramago.

Jose Saramago.

What can be said about this man’s prose and the way that it swallowed me completely – in a way that I never thought a novel would. A man whose prose is perfectly collected from the vastness of the Portuguese language (and then, almost more impressively, translated into the rhythm of the English language) and descriptive. Reading him earlier this summer was like having my language opened up and turned out, and then ground up, and then new words opened up somehow and you didn’t know that they existed and they are on your plate and they are perfect. Jose Saramago is like a new kind of food, using the same ingredients you have always used, but arranging them in such a manner that they taste completely, perfectly different.

I add these three to the list that already exists, containing J.M. Coetzee and Alice Munro.

These five pillars of the literary experience, must be read. If you are unfamiliar with them, collect them. Consume them and digest them and let them alter you. They are fine, fine writers who make worlds believable.

Where have I been?

I’m sorry for the past year. I’ve been lost in school work, and work, and school. I’ve not been talking to you at all. I’m thinking you may forgive me, provided I try to make you a part of my life again. Which is what I want to do, and which is what brings me here.

I’ve not stopped reading. I’ve read some really great works of art. Stuff that I always wanted to discuss with you. But I didn’t have the time, and to do so now would seem like I was lying to you about the books that I recall but can’t honestly review at the moment. But I have an idea for what to do with that – look forward to a new, paragraph series.

So what is it that has brought me to you today?

Nadine Gordimer. In about 20 minutes I will be finishing my first novel by her – more of a novella. And I want to write about it.

And about book stores.

And other authors that I’ve found myself attracted to in the past year.

So, if you’ll forgive me, I will begin again soon.

its bed time

but i just wrote an introduction to my prospectus. completely revised.

i’m playing into the need for the study a bit more – though i’m still not sure that the ‘so what’ for the study is coming through just yet. this is because i don’t have any questions right now. everything is, instead, just a statement. my questions are statements.

so i’m curious if i need a question.

i read the introduction to one of mark’s books this past week. aside from the fact that reading it was a very humbling experience (damn, is he ever a good historian), but i took note of the approach. he started with a question – broad. very broad. ‘Why is there no socialism in North America?’

thats broad.

then he went into the historiography – attempts to answer this question. then he attaches it to his topic (labour unions and leadership). this is how i found out that there was a need for his study. he dealt with the historiography before introducing his topic.

the wonderful thing is that his work will be of great value to the section of my study that he says i need to engage – leadership in the working class. so this has more value than just the style of his introduction. i just thought i would mention it as something that really quite captured me.

question. broad exploration. explaining the schools of thought. his topic of study. explaining the purpose of his micro-history within this general theme.

with another hour or two of work, this draft of my introduction will be done. tomorrow.

Dear Neal

Dear Neal.

– Yes, faithful reader of my blog (assuming you are out there).

How are you doing these days?

– I’m a little burdened with school work. Distracted from this blog, that’s for sure.

I’ve noticed.

– My apologies. I wish I could say that I will try harder in the future, but no matter how hard I try, I can only envision my commitment being even more and more challenged. Try not to hold it against me.

I’ll try.

– Thank you.

Other question.

– Shoot. I can take whatever you throw at me.

Where did you find that book that you’re currently reading? It is really, absolutely, a book that I have never heard of before.

– That, oh! faithful reader, is a great question. Have you ever heard of the Giller Prize?

Of course I have!

– Wonderful! Well, on the same day that the Bookers released their short list, the Gillers released their long list! It was a great list (seriously, the amount of quality writing that came out of Canada this year is pretty shocking). This is one of the listed nominees. I’ve got high hopes for it.

Why did you pick that out of all of the possible books?

– I don’t have a great answer for that. The CBC Book Club website has a contest running where you can make suggestions for the short-list. Not that they will actually be taken by the adjudicating committee, but they are very interesting to read. And this is one of those books that keeps popping up. Over and over and over again. People, the lay people of reading, people like you and I, seem to love this book. So I picked it up (knowing that I don’t need another book for a very, very long time), and have enjoyed it as both a source of serious reading as a distraction from the nonfiction that has been completely sucking up my life.

But why not something else? Like one of the listed books that you already own?

– Good question.

That isn’t an answer.

– I know. I even own many of those already. Haven’t read them. Need to do that, I suppose. This one really caught my eye (and I didn’t even know it was a collection of short stories until after I had it in my bag on the bus ride home from the book store). Not that the others haven’t, but… well… you know how that goes.

What else was listed?

– Last question I can answer tonight. I’ve got reading to do.

- David Bezmozgis for his novel, THE FREE WORLD, HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

- Clarke Blaise for his short story collection, THE MEAGRE TARMAC, Biblioasis

- Lynn Coady for her novel, THE ANTAGONIST, House of Anansi Press

- Michael Christie for his short story collection, THE BEGGAR’S GARDEN, HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

- Patrick DeWitt for his novel, THE SISTERS BROTHERS, House of Anansi Press

- *Myrna Dey for her novel, EXTENSIONS, NeWest Press

- Esi Edugyan for her novel, HALF-BLOOD BLUES, Thomas Allen Publishers

- Marina Endicott for her novel, THE LITTLE SHADOWS, Doubleday Canada

- Zsuzsi Gartner for her short story collection, BETTER LIVING THROUGH PLASTIC EXPLOSIVES, Hamish Hamilton Canada

- Genni Gunn for her novel, SOLITARIA, Signature Editions

- Pauline Holdstock for her novel, INTO THE HEART OF THE COUNTRY, HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

- Wayne Johnston for his novel, A WORLD ELSEWHERE, Knopf Canada

- Dany Laferrière for his novel, THE RETURN (translation, David Homel), Douglas & McIntyre

- Suzette Mayr for her novel, MONOCEROS, Coach House Books

- Michael Ondaatje for his novel, THE CAT’S TABLE, McClelland & Stewart

- Guy Vanderhaeghe for his novel, A GOOD MAN, McClelland & Stewart

- Alexi Zentner for his novel, TOUCH, Knopf Canada

*READERS’ CHOICE

But Neal, what does that *Reader’s Choice mean!?!?? I am so curious!

– Save that question for next time. A good story about that, and the novels that I picked up as a result of it. Until then, go check out one or two or six of these novels. So many of them are definitely worth checking out.

Oryx and Crake – Margaret Atwood

I have a first edition of this book. Meaning it was purchased for me upon its release by my mother and I had not read it until quite recently. Does that strike you as ridiculous?

Margaret Atwood is a fantastic writer. I don’t think I need to add my voice to the symphony of voices that argue this. That said, there is a fairly strong listing of people who feel quite differently – who can’t appreciate her. They often cite her science fiction as the reason for this. ‘Science fiction’.

Margaret Atwood is a fantastic writer. I don’t think I need to add my voice to the symphony of voices that argue this. That said, there is a fairly strong listing of people who feel quite differently – who can’t appreciate her. They often cite her science fiction as the reason for this. ‘Science fiction’.

Margaret is quite well known for not enjoying this term when it is assigned to her novels. ‘Science fiction’ does not capture her intentions quite in the way that she wants them to be captured by the genres of literature. She suggests ‘social science fiction’ – a term that has floated around some authors for quite some time, but that just has not latched onto by the industry that survives because of them. Perhaps this is why even her ‘science fiction’ novels are found in the general fiction section of the book store.

I’d never previously read any of her ‘science fiction’. I actually tend not really read science fiction, though not for any good reason. It is very rare that a good piece of science fiction does not thoroughly impress me. Particularly those that are of a dystopian nature – or of a political future that is terrifying. Margaret has managed to capture that sensation in this book. I was frightened about the world that this book created. Or didn’t really create.

Because it is set in the future. The very near future. It makes references to culture and technology that, over the past decade, has come to dominate our lives. Addiction to science and striving for more, dangerous contagions around the world, genetic modification and the promise of containment that we don’t really and can’t really trust, the destruction of the entire race of humanity. The creation of a new race. The nondestruction of the entire race (are there really more out there?).

And it is a story told through relationships that were never quite comfortable. A world without comfortable relationships, and terrifying social and moral ills. That is the world in which you find yourself as a reader – but it feels like maybe, just maybe, this world is set in the tomorrow. The immediate tomorrow. And that is frightening.

The protagonist, Snowman/Jimmy (a naming scheme that is so fantastically used throughout the novel) was good friends for years with Crake (whose other name is ultimately not important). Crake is a genius – a certifiable genius. Top-performing student, given particularly strong financial backing from the corporations that own him and his work. But he is inhuman – perhaps. Morally that is. And he tries to become a god, a creator of new bioforms.

And succeeds.

His greatest success is the small colony of the new race/species/beings that Jimmy/Snowman saves from total annihilation just as the world is starting to end. Does this make sense? Am I communicating this well? Probably not. But Snowman is tasked with having to outline this world to this new species – and does so by using language. Jimmy was talented with language – he went to an arts school rather than a science school. He knows how to manipulate and use words to make the world buy things they don’t need but think that they really want. And that skill serves him well in his new position of oracle between the race and their two Gods, Oryx and Crake.

Does this make sense? It didn’t make sense to me. And I don’t want to say much more, because I don’t want to give away anything of the story. Everything meets together in a really exciting way in this book, and it is revealed masterfully (this is Atwood that we are talking about). Eventually it does make sense, too. Mystically and mythically. The world gets reborn, but not with hope – with the reality of a rebirth created by man – a species that doesn’t exist any longer (mostly doesn’t, anyways). And the world that is reborn is not really one that most would want to live in. At least, not one I would want to live in.

Recommended. Part one of an unconnected trilogy of books that I will have to read (the final part being Atwood’s next novel to be published).

I will leave you with an excerpt. Because Atwood is worth reading – even if it is only on a blog:

“I am not my childhood,” Snowman says out loud. He hates these replays. He can’t turn them off, he can’t change the subject, he can’t leave the room. What he needs is more inner discipline, or a mystic syllable he could repeat over and over to tune himself out. What were those things called? Mantras. They’d had that in grade school. Religion of the Week. All right, class, now quiet as mice, that means you, Jimmy. Today we’re going to pretend we live in India, and we’re going to do a mantra. Won’t that be fun? Not let’s all choose a word, a different word, so we can each have our own special mantra.

“Hang on to the words,” he tells himself. The odd words, the old words, the rare words. Valance. Norn. Serendipity. Pibroch. Lubricious. When they’re gone out of his head, these words, they’ll be gone, everywhere, forever. As if they had never been.

Many Books on the Booker List

I have to be honest. I’ve not yet read anything on the Man Booker Prize longlist. I own two or three of the novels that made it that far, and, as explored when the longlist was announced, I was interested in quite a few more. But I’ve not yet done anything with that. I’ve been distracted by other things I suppose – other books, other parts of life, moving across my country. Those kind of things.

That does not change the fact that I should be reading some of these books so that I can actually partake in the general literary discussion that is taking place right now with the release, yesterday morning, of the Man Booker Shortlist:

-

The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes

-

Jamrach’s Menagerie by Carol Birch

-

The Sisters Brothers by Patrick deWitt

-

Half Blood Blues by Esi Edugyan

-

Pigeon English by Stephen Kelman

-

Snowdrops by A.D. Miller

I’m actually quite excited about the top half of the list, and less interested in the bottom half. I’m still wanting to read The Last Hundred Days by Patrick McGuinness above pretty much all of the other ones, but it still has not been released here in Canada. I have not even heard about it having a release date. But the premise sounds so interesting – I really would like to read it.

Half Blood Blues is probably riveting. I’ve heard good things about Pigeon English (and the cover is so very, very sexy), and Snowdrops is so very far out of my traditional genre that I may just have to give it a chance. But the top three – Jamrach’s Menagerie, The Sisters Brothers, and The Sense of an Ending are totally topping the bottom three in terms of personal interest, with The Sisters Brothers probably topping the list for me. I’m hoping to finish up Hunger by Knut Hamsun this week so that I can start that book up sooner rather than later.

Midnight’s Children – Salman Rushdie

“The moment I was old enough to play board games, I fell in love with Snakes and Ladders. O perfect balance of rewards and penalties! O seemingly random choices made by tumbling dice! Clambering up ladders, slithering down snakes, I spent some of the happiest days of my life. When, in my time of trial, my father challenged me to master the game of shatranj, I infuriated him by preferring to invite him, instead, to chance his fortune among the ladders and nibbling snakes.

All games have morals; and the game of Snakes and Ladders captures, as no other activity can hope to do, the eternal truth that for every ladder you climb, a snake is waiting just around the corner; and for every snake, a ladder with compensate. But it’s more than that; no mere carrot-and-stick affair; because implicit in the game is the unchanging twoness of things, the duality of up against down, good against evil; the solid rationality of ladders balances the occult sinuosities of the serpent; in the opposition of staircase and cobra we can see, metaphorically, all conceivable oppositions, Alpha against Omega, father against mother; here is the war of Mary and Mura, and the polarities of knees and nose… but I found, very early in my life, that the game lacked one crucial dimension, that of ambiguity – because, as events are about to show, it is also possible to slither down a ladder and climb to triumph on the venom of a snake… Kepping things simple for the moment, however, I record that no sooner had my mother discovered the ladder to victory represented by her racecourse luck than she was reminded that the gutters of the country were still teeming with snakes.”

I have a secret. When I am reading a book and come across a particularly impressive passage – something that strikes me for any number of reasons – I turn up the bottom corner of the page. Many people say that this is some form of cruelty to the book and the author; to me, it is a way of coming back and reading some of my favourite parts again.

About 150 pages into Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie’s magical realist epic and the winner of the 1981 Booker Prize, the Booker of Bookers and the Best of the Booker prize, I realized that I was going to have too many page corners turned up. At the time it didn’t hit me that this meant I was going to want to read the book again; in retrospect, I don’t think it can possibly mean anything else.

About 150 pages into Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie’s magical realist epic and the winner of the 1981 Booker Prize, the Booker of Bookers and the Best of the Booker prize, I realized that I was going to have too many page corners turned up. At the time it didn’t hit me that this meant I was going to want to read the book again; in retrospect, I don’t think it can possibly mean anything else.

As far as modern literature goes, Midnight’s Children may actually be legendary. Through the story of and experiences of a boy convinced of his own importance and failure to achieve his potential in the tides of history, we discover the birth of an entire sub-continent. India and Pakistan free themselves of their colonial shackles in the first section, with Bangladesh doing so (no longer being administered by Pakistan) in the second (or was it the third?). And, goodness me, does Mr. Rushdie ever manage to produce a world where it is just plausible enough that his character, Saleem Sinai, is the centre of the universe – the hinge upon which a new nation grows and succeeds and fails.

Saleem is one of the Midnight Children; those 500-and-some children who were born in the midnight hour of India’s birth. Saleem, though, is one of only two of these children born at the very instant that the hands of the clock met at midnight. As all of these 500-and-some children are imbued with some form of magical power, it would only make sense that Saleem and his midnight-specific partner would have the most impressive magical powers; that these two would be diametrically opposed to each right from the beginning is merely brilliant plot production. And human deformations – don’t forget about those. Like all details in this novel, they play a very important part. This is how the magical aspect of the novel starts and develops. The realist part is very different.

The realist part hinges on history – that experienced by generations of family created and destroyed by nations that have never managed to be united and never managed to be separated. The story is presented as an oral memoir, told by Saleem to one of his servants (or admirers?), starting thirty-two years before the beginning of the Saleem’s life and ending thirty-two years afterwards. We meet his grandfather, a doctor trained in western medicine but living in the valleys of Kashmir. We meet his grandmother, a woman veiled in a white sheet with a small hole – frequently ill. We watch the two of them meet and fall in love and then, dramatically and immediately, fall out of love.

It is with this that the history of Saleem and the history of his entire continent is told. Symbolism, metaphor, history represented by magical impossibilities that are entirely unlikely but so impressive. And oftentimes you have no idea whatsoever that it is happening. In fact, there are moments where you are downright confused by Salman Rushdie’s direction. There will be moments when you will be angry at him. Tempted to put the book down and never pick it up again. And each time that he shows you that you can trust him your resistance to your frustration builds; if this isn’t your experience, all I can do is tell you to push through. Finish this book.

I encountered this almost road block at the end of the second part of the book. I was lost. I had no idea what story was being told – why it was being told. An enormous event had just taken place. I had no idea where Saleem, or Mr. Rushdie, would go. But I battled through this. And I am so grateful for having done so – the way that the book wraps up in the end is incredibly moving. Devastation filled with every gratuitous word possible, acts and crimes committed against Saleem by the Indian state in a state of emergency (remember, this is a historical novel – don’t allow yourself to forget this). And it hurts to read of how the Midnight Children, tied down to their fates by the hour of their birth, discover this pain that they assumed they were immune to. And, despite this, a spring of hope and a promise for a future. Your joy will be overwhelming.

And none of this is without purpose. Saleem Sinai’s story brings into question enormous questions of social science and history by providing a history. And, similar to Yann Martel’s Beatrice & Virgil, which I read earlier this year and recommend, it tells history in an incredibly unconventional but entirely meaningful way. And it is not just the history of an individual – somehow Mr. Rushdie truly manages to tell the history of the country through a single man’s experiences. The intricate nature of the novel is so impressive not only in the detail but in how the detail is used – historical realism this may not be, but effective realism it is.

Early in the novel Saleem instructs his servant (who, I believe, is actually meant to be the reader personified in the novel), “To understand just one life, you have to swallow the world.” This novel is an impressive product of this philosophy – easily the most convincing of all of the books I have read this year, perhaps the most convincing of all the books I have ever read. I love this book more in restrospect than I did while I was reading it, but I was enamoured with it while I was reading it because I wanted to know how Salman Rushdie’s world of details that were yet to be resolved was going to be resolved. Do I recommend it? Absolutely! But prepare yourself for an endurance run of an novel that is, perhaps, the most difficult read you’ve ever read – and fight every urge to set the novel aside and never pick it up again. Every investment you put into this book will astound you with its returns.

How to follow up and not yet a review.

How do you follow up a work like Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children? It is a pretty unique reading experience and it leaves you aghast. Absolutely aghast.

I keep on thinking about what Mr. Rushdie managed to accomplish in those 550 pages that I read. And the reality is that he accomplished so much more than I can begin to comprehend. Everything seems so valid in that novel. Everything that is included tells a story and, though you don’t realize it at the time, those minor details of character and description that he puts into the first hundred pages (then again in the next hundred, and the next hundred, and the next hundred) will come back later. You don’t believe it at the time, but it happens. And rocks your mind afterwards.

Just as my experience earlier this year with magical realism did (Everything is Illuminated), I did not know what to do afterwards. I have been reading Pat Barker’s The Ghost Road, but it took me a long time to get into it. I had to reread the first thirty pages a few times because I just did not care. I had no recollection of the few events that had already taken place. My mind was still festering on the previous book. I could not move on.

And it still happens every now and then (though I must say that I am very much enjoying The Ghost Road and expect to finish it this evening – it is lying beside me at the moment just waiting to be picked up). Midnight’s Children is a startling novel, that will challenge you and everything you know about literature. I don’t know how to even begin to review it.